Maladies and Medicine on 19th Century Whaling Ships

A Collections Chronicles Blog

by Carley Roche, Associate Registrar, Collections and Exhibitions

July 27, 2023

Like many others, I have a slight fear of going to the doctor. The poking, prodding, and questioning always makes me feel uncomfortable—despite knowing that it is necessary and safe. Regardless of this fear, I would gladly visit 100 doctors today rather than one doctor on a whaling ship in the mid-19th century.

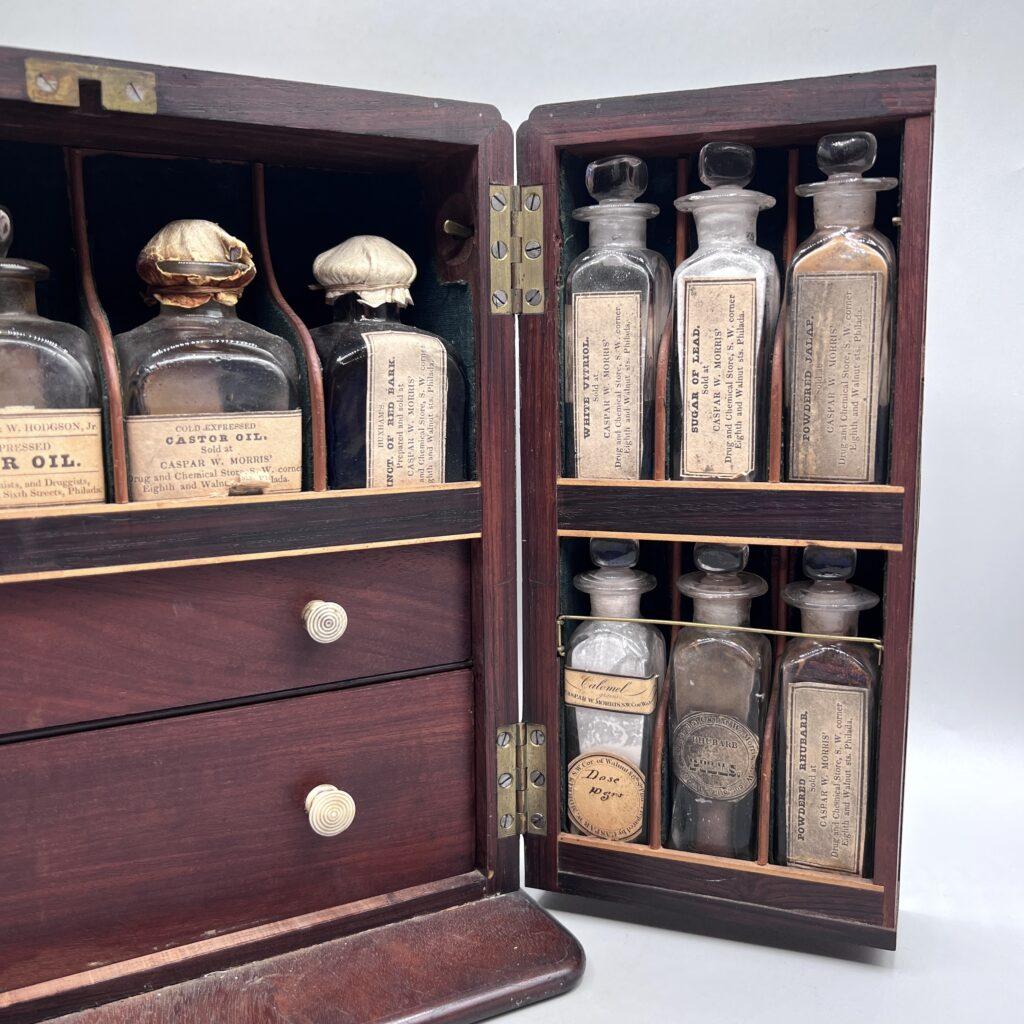

Why am I coming to this conclusion now when my work in the Museum’s collection storage area has never required a doctor’s visit? Recently, while completing a routine condition report on a whaling ship medicine cabinet in the collection, I discovered something new about the object: how to open its left door! A previously unknown mechanism needs to be pressed ever so gently in order for the cabinet to completely open up. Now, with its contents newly revealed, I was able to take a full inventory of the 19th century medicine held inside. Suffice to say, I am grateful for modern medicine.

“Medicine Cabinet” ca. 1850. Gift of the J. Aron Charitable Foundation, 1988.075.0120

With the newly opened cabinet, I discovered a whole host of items hidden behind the previously locked door. Each door holds six vials of medicine on two shelves, two previously hidden vials are now accessible on the center shelf and, for the first time, I could open the two drawer’s inside the cabinet. With an incredible trove of new information at my fingertips, I began to take a closer look at the newly available contents.

I found some vials to be completely empty, some with varying amounts of powder or liquid inside, and some that are still sealed and completely full. Thankfully, all of the labels are still present and legible so that I could note what the medicine is.

Beginning with the left door, as the items stored here were only just revealed, I found mostly unfamiliar medicines including Paregoric, Sweet Spirits of Nitre, Elixir of Vitriol (liquid), Anitibilios Cathartic Pills, and Tartar Emetic. Only one of the six labels did not confound me: Essence of Peppermint.

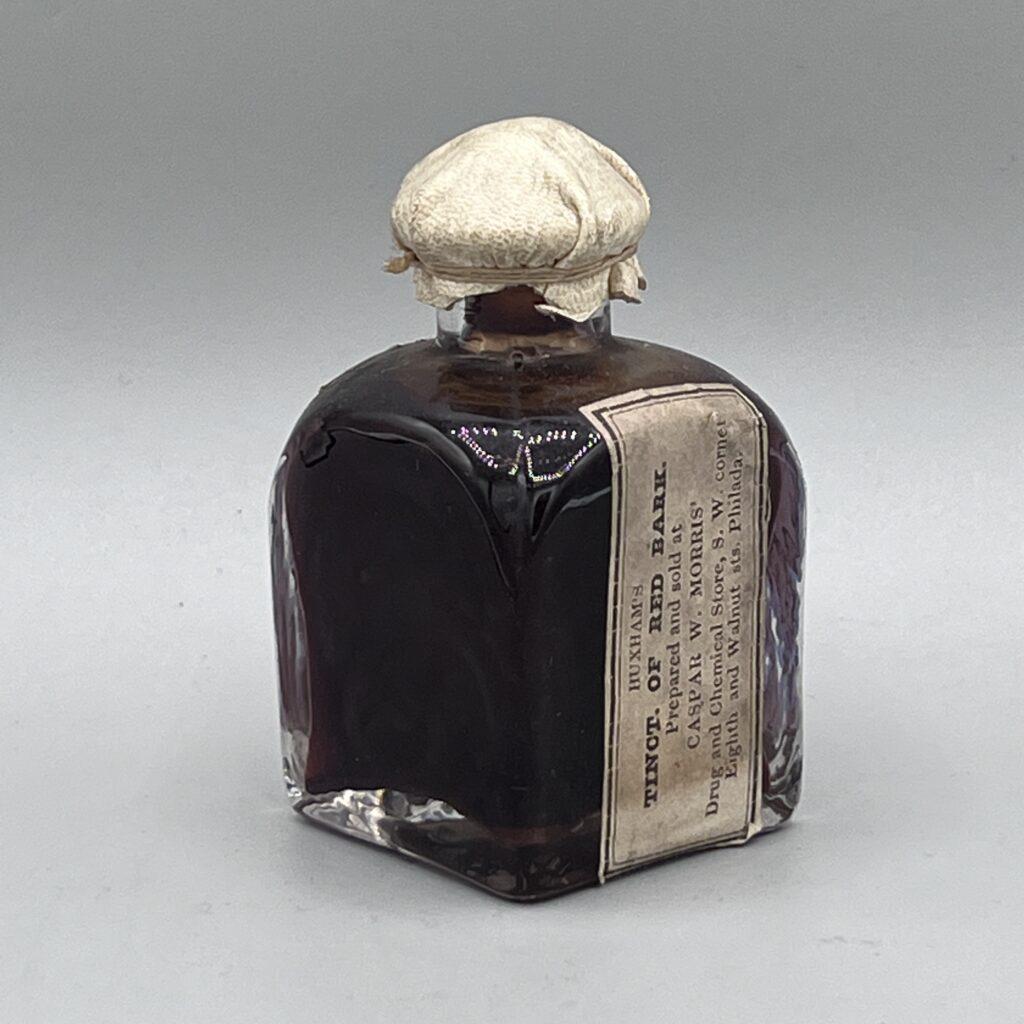

Moving on to the main center section of the cabinet, I now had access to two previously unseen containers: Warner’s Cordial (liquid) and Cold Expressed Castor Oil. The other two vials—a second Cold Expressed Castor Oil and Tincture of Red Bark (liquid)—could be accessed previously when the right side door was open.

Two drawers take up the rest of the center section, both containing a mix of medicine and medical supplies. The top drawer holds adhesive plaster, brass weights, a portable scale, Tincture of Sulphur, Assafoetida [sic] Pills, Wistar’s Cough Lozenges, and a mother of pearl spoon. The bottom drawer holds a small leather case with nine vials of various pink pills, Humphreys’ Homoeopathic No. Five for Dysentery, an empty large flat vial, 12 empty small vials, two jars of Turner’s Cerate, a vial with an unknown oil, two jars of Red Precipitate Ointment, blistering ointment, and a glass mortar and pestle.

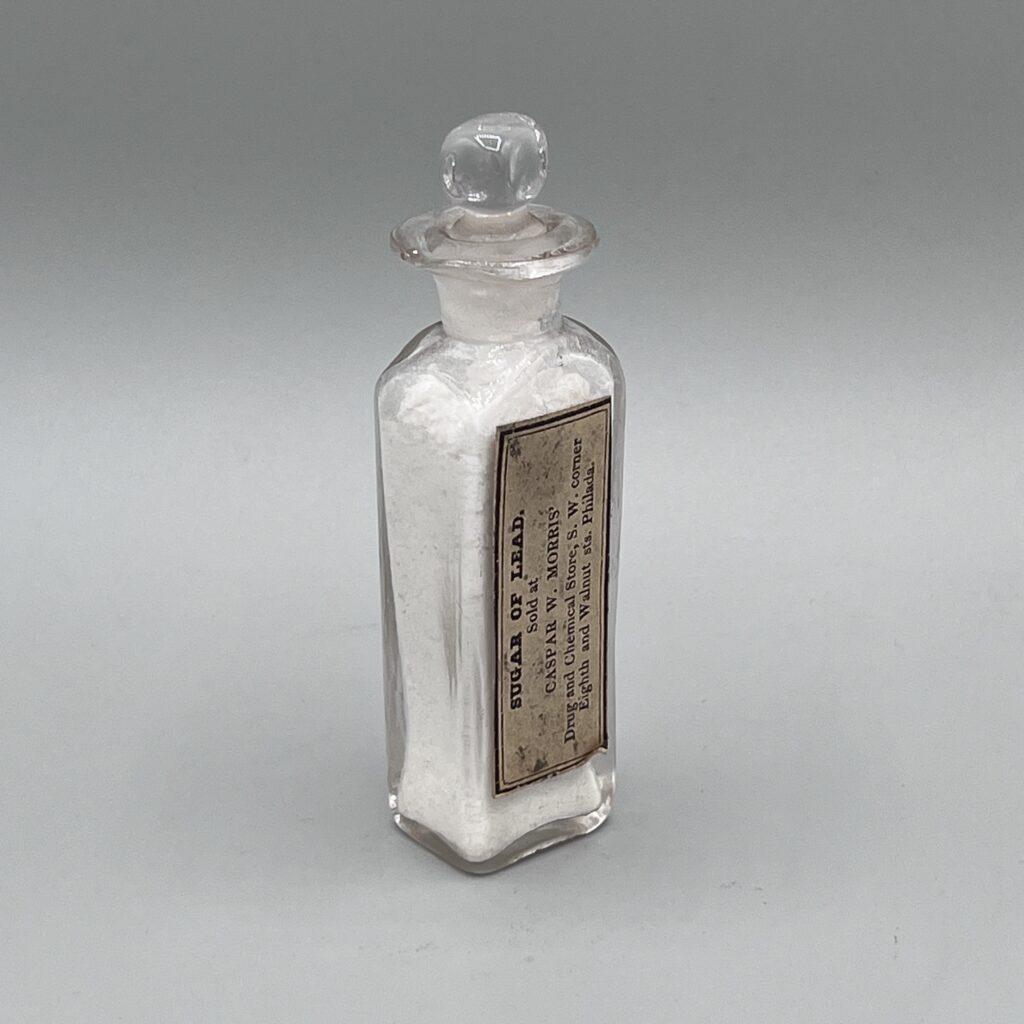

Although the right door’s containers were previously accessible, it would not be a complete catalog of the medicine cabinet without double checking its contents. Here, I noted more interesting medicine including White Vitriol, Sugar of Lead, Powdered Jalapeno, Calomel, Rhubarb, and Powdered Rhubarb. Quite the inventory for such a modest space!

19th Century Medicine vs 21st Century Fears

I will be the first to admit that I do not have an extensive knowledge of modern medicine. I know the basics to stay healthy, but my interests always veered towards history and the arts rather than chemistry and biology. Even with this in mind, I had to pause twice while completing the above inventory due to fears of exactly what I was coming into contact with. I quickly grew concerned that the standard nitrile gloves I was wearing would not be enough to protect me from centuries old medicine.

The first time I stopped working, I had barely begun to simply read the labels. Sugar of Lead mixed a common harmless word with a known modern danger, while items such as Elixir of Vitriol and Sweet Spirits of Nitre simply confounded me. Before continuing I knew I had to step away from the cabinet and research whether or not its contents are detrimental to my health, the health of other staff members, and to the collection as a whole.

After thoroughly washing my hands and researching the medicines and their uses, I came to the conclusion that my health was not at risk. Many of the medicines—and I am using this term loosely—were developed to induce vomiting or the release of one’s bowels. This will only occur today if I choose to ingest a large amount of the vials’ contents and, thankfully, I have no desire to consume anything from over 200 years ago. My fears put to rest, I felt safe in continuing my work.

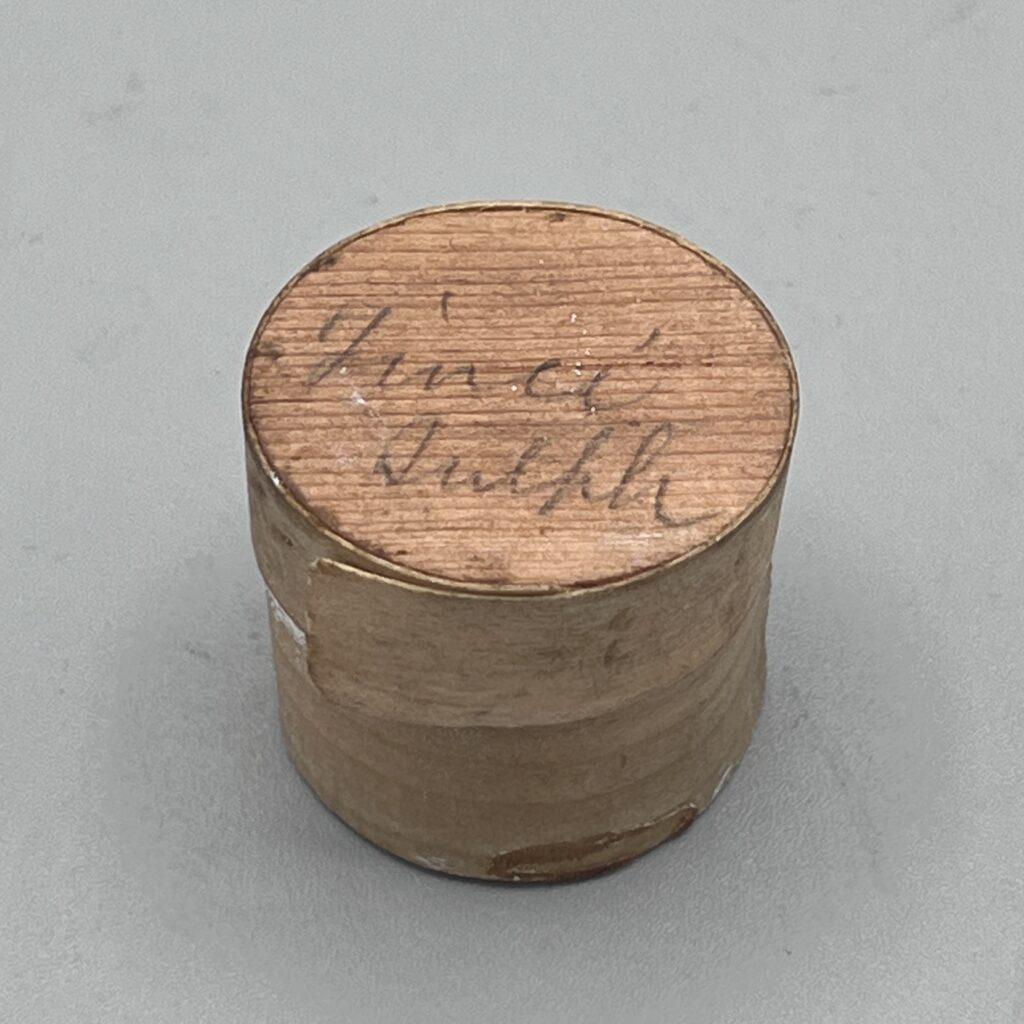

Almost immediately, I had to stop once again. Moving on to inventorying the drawers, I found loose white powder upon opening the top one. A quick check of the bottom drawer and the cabinet doors proved the powder is contained to this drawer, which also holds a small container with white powder inside.

Reading the handwritten label on the lid, “Tinct Sulph [sic],” I found myself in contact with powdered sulfur. Due to my lack of knowledge in chemistry, I quickly stepped away from the drawer and began to research any negative effects of sulfur. The good news is I had nothing to fear because sulfur is a natural ingredient used in medicine for centuries that continues to be commonly used today. With this in mind I elected to keep the powder as is in the drawer so as not to risk spreading it elsewhere, either in the medicine cabinet or throughout collection storage.

Medical (Mal) Practice in America

Let’s take a step back and put this cabinet into its historical 19th century context. Medicine at the time still held many homeopathic and botanical roots—as seen with the Powdered Rhubarb, Tincture of Red Bark, and Powdered Jalapeño inside—but breakthrough inventions such as the stethoscope (1816), quinine (1820), and aspirin (1897) alongside the emergence of germ theory radically altered the field of medicine during the 19th century.

Many of these advancements emerged in Europe thanks to a structured educational system. By 1800, America only had four medical schools—University of Pennsylvania, King’s College (Columbia University), Harvard University, and Dartmouth College—but anyone could call themselves a doctor without matriculating from these institutions due to a lack of regulation. Those who sought a proper medical education traveled to Europe where they discovered just how far behind America was in comparison. Calls for immediate educational reform occurred upon these students’ return to the United States.

In response, medical schools began materializing almost overnight, which followed a system of lectures, three-to-four-year apprenticeships, and no admission requirements. This proved to be a glaring problem because these institutions awarded anyone a doctorate degree so long as they paid the required fees. A graduate did not need to understand the human body and how to treat it; they just needed to exchange money for a diploma. Once again, reform was called upon, but this time from the public who became agitated as these “doctors” charged exorbitant fees for lackluster care.

The mid- to late-19th century saw official changes across America’s medical education and regulation. In 1847, the American Medical Association was founded and began implementing tight restrictions on educational institutions in an effort to end the pay-for-diploma system. The opening of Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland, in 1876, is the benchmark for the start of America’s modern medical education system—now globally respected.

Battling Sickness and Injuries at Sea

Despite this tumultuous medical history, sailors had a job to do no matter what advancements or hindrances were happening ashore. The particular medicine chest that is described above is believed to have served on the whaleship Cherokee. A barque whose home port was in New Bedford, Massachusetts, but traveled as far as Alaska, Hawaii, and New Zealand throughout her career. As part of the whaling industry, Cherokee and her crew endured dangerous and brutal conditions. Ships could be away from their home port for months to years at a time during which sailors suffered from disease due to poor hygiene, pests, and a general lack of medical knowledge. On top of this, crew members risked loss of limb and death with day-to-day tasks manning the ship, natural disasters at sea, and, of course, the dangerous act of hunting whales.

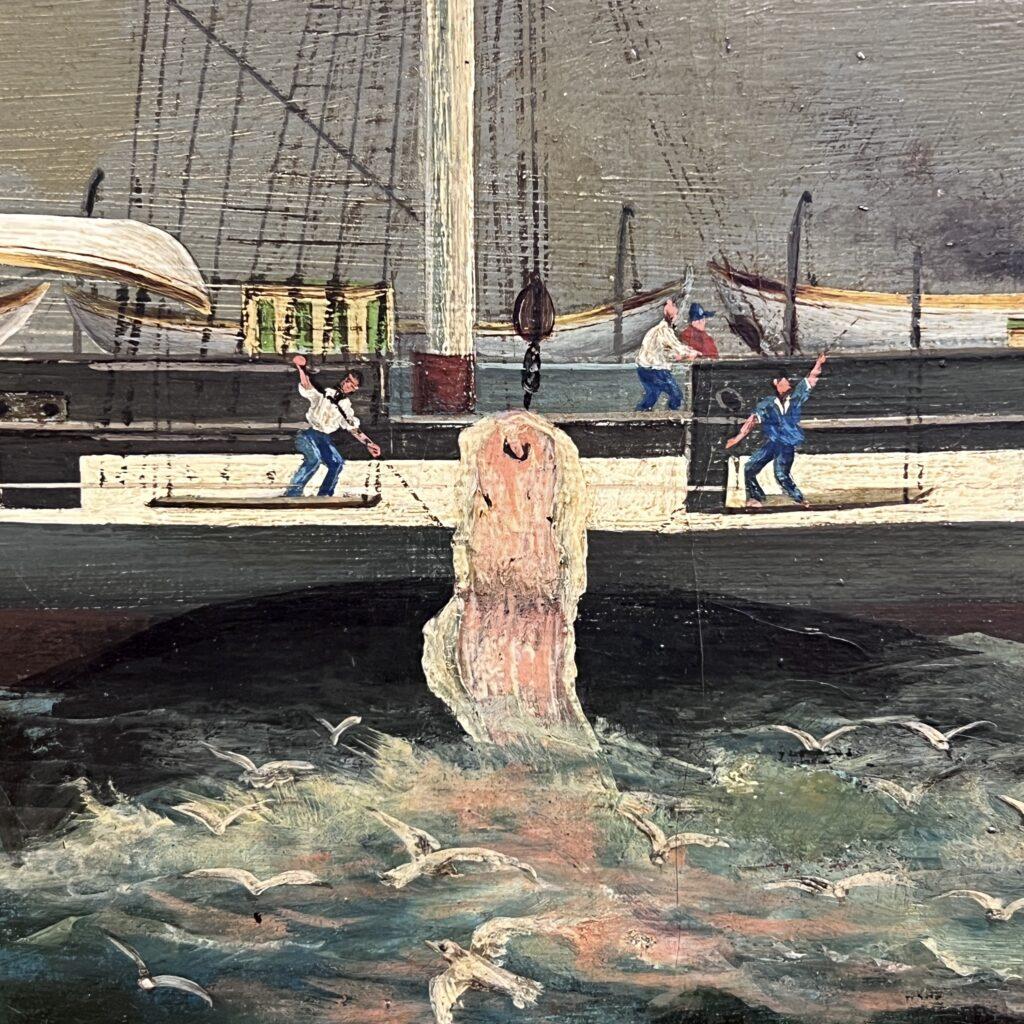

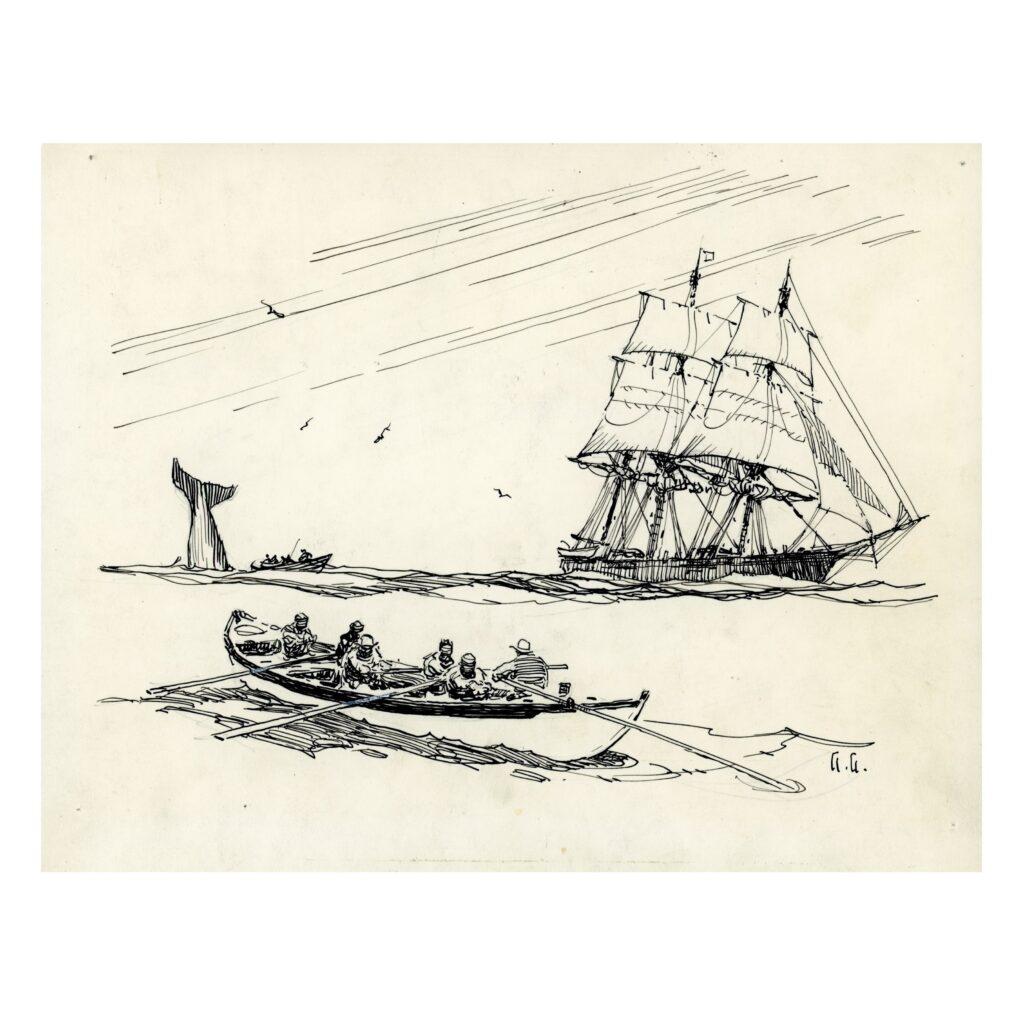

Left: detail of “Eliza Adams of New Bedford Cutting in a Whale”, mid 19th century, by Charles Braddock Gifford (1830-1888). Peter A. and Jack R. Aron Collection, South Street Seaport Museum Foundation 1991.068.0087

Right: [Whaling Scene], mid 20th century, by Gordon Grant (1875-1962). Seamen’s Bank for Savings Collection. 1991.071.0125

Thanks to one of the earliest labor laws passed by Congress—the Act for the Government and Regulation of Seamen—Cherokee was required to carry a medicine chest on board. Passed on July 20, 1790, it states “every ship or vessel belonging to a citizen or citizens of the United States, of the burthen of one hundred and fifty tons or upwards, navigated by ten or more persons in the whole, and bound on a voyage without the limits of the United States, shall be provided with a chest of medicines, put up by some apothecary of known reputation, and accompanied by directions for administering the same.”

If one wanted to find an “apothecary of known reputation” in the 19th century they would want to travel to Philadelphia. A leader in American medical history, the city of Philadelphia is home to the nation’s first hospital and first medical school.

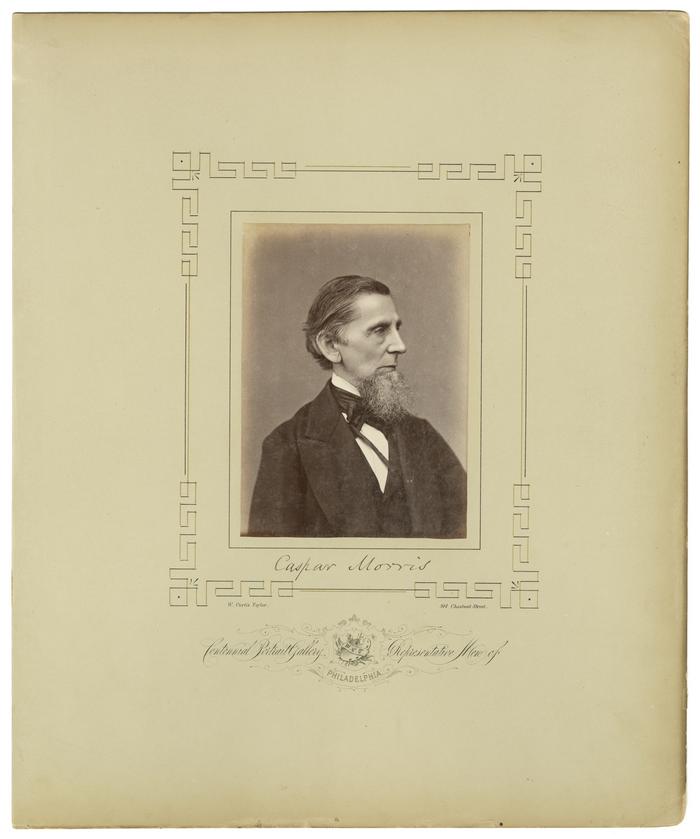

Looking at the labels on the vials and medical supplies in this cabinet, a majority are from a drug and chemical store owned by Caspar A. Morris (1805–1884) at the South West corner of 8th and Walnut Streets. Morris came from a prominent Philadelphian family and graduated in 1829 from the University of Pennsylvania. He was a trusted and respected physician who helped establish local health care institutions. Having medicines and supplies manufactured from Morris fulfilled the requirements of the law.

“Caspar Morris portrait, 1876” Herbert Welsh Collection. Collection of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

The issue is no longer having medical supplies on board a whaling ship, but whether or not an injured or sick person could even be properly treated. Typically, the physician on a whaling vessel was the Captain or his wife if she joined the voyage; neither were expected to have any medical training. Adding further complications, whoever held the title of “doctor” that day had to perform life saving procedures while on an unsanitary moving ship due to the nature of being away from port for months at a time. Whether a sailor was afflicted with scurvy, a toothache, or in need of an amputation, their life was in the hands of an ill-prepared person in unfit conditions. Life at sea was dangerous; disease and injury were deadly.

“Ship’s Surgeon’s Instrument Case” ca. 1831-1837. Gift of the J. Aron Charitable Foundation, 1988.075.0121.A-.O

I do not expect my slight fear of the doctor to go away overnight, even with a better appreciation for the advancements made between the making of this medical chest and today. The next time I receive medical care, whether on land or at sea, I will be able to feel more at ease knowing the healthcare profession has built itself up tremendously over the past 200 years.

It is interesting seeing the evolution of medicine; some of those found in the whaling ship medical cabinet would never be used today, while others have been significantly improved upon. I never anticipated this deep-dive into whaling medical history or the roller coaster of emotions that came with a routine condition report. Feeling intrigue, fear, excitement, and a sprinkling of disgust rapidly back-to-back certainly makes for an interesting morning in collection storage!

Additional Readings and Resources

A Medical Manual and Medicine Chest Companion by Thomas Ritter, M.D. 1847. National Library of Medicine Digital Collections. Accessed July 13, 2023

“Hazardous Materials in Your Collection” August 1998. National Park Service. Accessed July 12, 2023

Injury and Sickness at Sea National Museum of American History. Smithsonian Institute. Accessed July 13, 2023

Journal of the Cherokee (Bark) Out of New Bedford, MA, mastered by Jacob L. Cleaveland. Kept by Stephen D. Peirce. 1846-1849. Internet Archive. Accessed July 6, 2023

“Medicine and Science in the 19th and 20th Centuries” by Harry Bloch, M.D. 1988. Journal of the National Medical Association. Vol. 80 No. 2. Accessed July 13, 2023

Morris Family Papers. Historical Society of Pennsylvania. July 2007. Accessed July 6, 2023

“Nurses at Sea” by Nomi Dayan, May 2, 2019. The Whaling Museum. Accessed July 13, 2023

Research Policies

Conducting research is a vital part of the Seaport Museum’s work. The Museum is actively engaged in a complete inventory of its collections and archives. This ongoing project will improve future public access to the materials in our care and ensure that items are documented and preserved for future generations.